Bread Protests

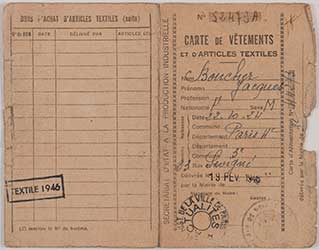

Protests against so-called "domestic" shortages mobilized women and children, often in small numbers. The first occurred during the winter of 1940-1941 almost exclusively in former communist municipalities of the Department of the Seine.

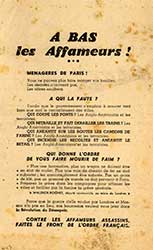

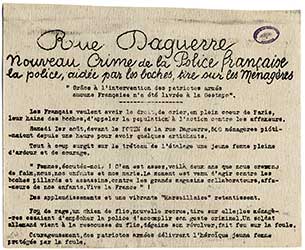

These protests, some of which were undeniably spontaneous, seem to have been direct results of popular emotion and problems with basic subsistence. They often began in the markets, where the absence of a product constituted the triggering element. The fact that they were common in former communist areas nevertheless invites exploration of their degree of spontaneity. The Communist Party mobilized people in these areas early and enduringly in the Occupation. This form of mobilization, which no other Resistance movement encouraged or elicited, was grounded in social discontent that the authorities themselves acknowledged and that clearly influenced public opinion and involved a segment of the population that was far more complicated to crack down on than others. These movements publicly confirmed the fact that certain expressions of discontent were possible in broad daylight.

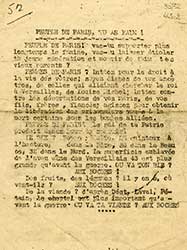

During the winter of 1941-1942, these protests occurred outside pre-war militant areas and helped to undermine the popular consensus that Vichy was attempting to create. They became explicit components of the organized Resistance and its activities; protesters later broadened their demands (including rejection of the STO [Service de travail obligatoire/forced labor program], for example). Protests were sometimes called for by communist movement women's committees and, in some cases were part of preparations for the strike on July 14, 1944 and the insurrectionist strike in August of the same year.